Vascular access

Central venous access

It’s not possible to textually teach someone how to establish central venous access. For this, we have Youtube. But there are important things to know about when we might want to pursue central venous access, and pitfalls to look out for. So when might we be interested in pulling the trigger and saying, “You know what? Today’s the day to poke a bigger hole in this patient than usual”?

- The patient is a really hard stick, maybe because his/her vasculature is all kinds of screwed up from drug use, or because the patient is morbidly obese and finding peripheral veins is just not possible to do without subjecting him to role-playing a pincushion.

- Special drugs like vasoconstrictors or total parenteral nutrition

- Need for a multilumen catheter to deliver a bunch of medications at once

- You need access for a really long time, longer than a peripheral IV is expected to last

- You need to do something special, like dialysis or float a Swan-Ganz catheter

Fortunately for us, even in patients with bleeding/coagulation disorders, central access is not contraindicated1. We just need to be a little more careful.

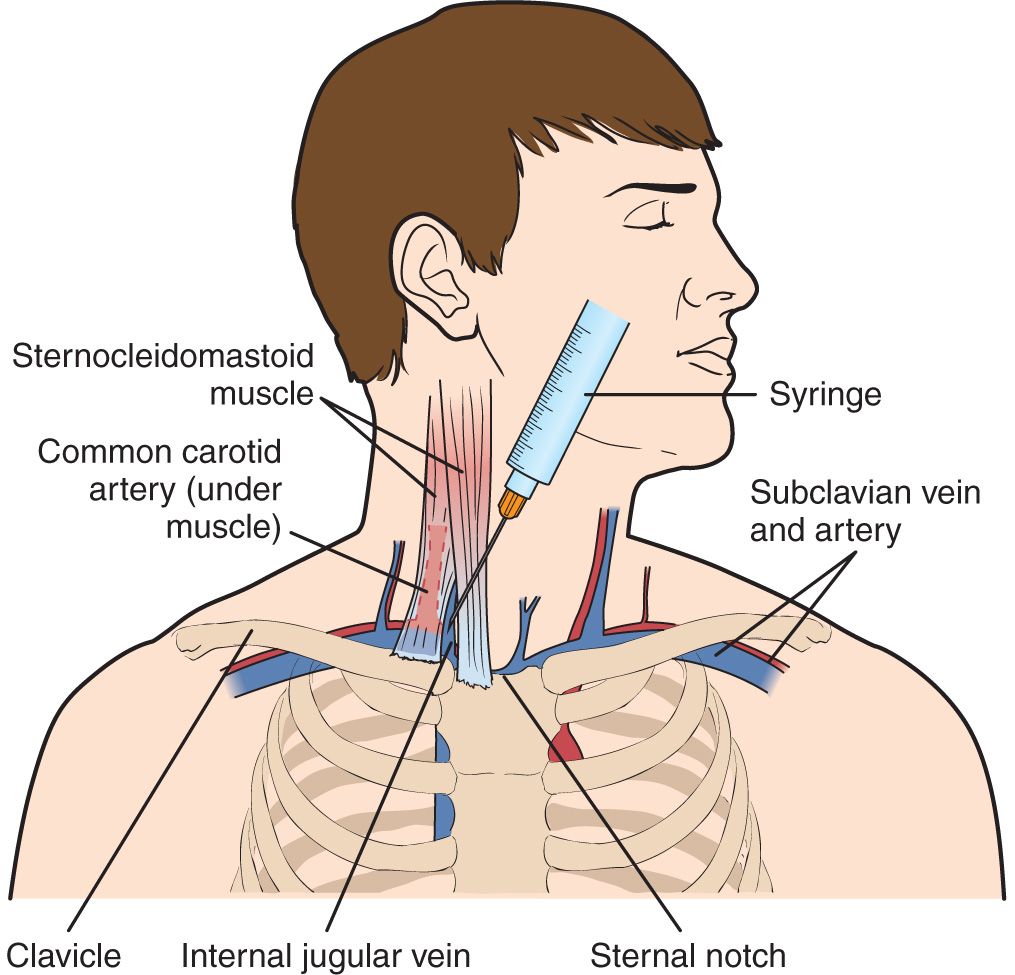

Internal jugular vein

- So you’ve just punctured your patient’s carotid artery while trying for jugular venous access. What do you do? Answer: just remove the small-bore probe and compress the neck for 5 minutes. Compress for longer if your patient has risk factors like a coagulopathy.

- So you’ve cannulated the carotid. This is different and requires vascular surgery to come. The patient could stroke2.

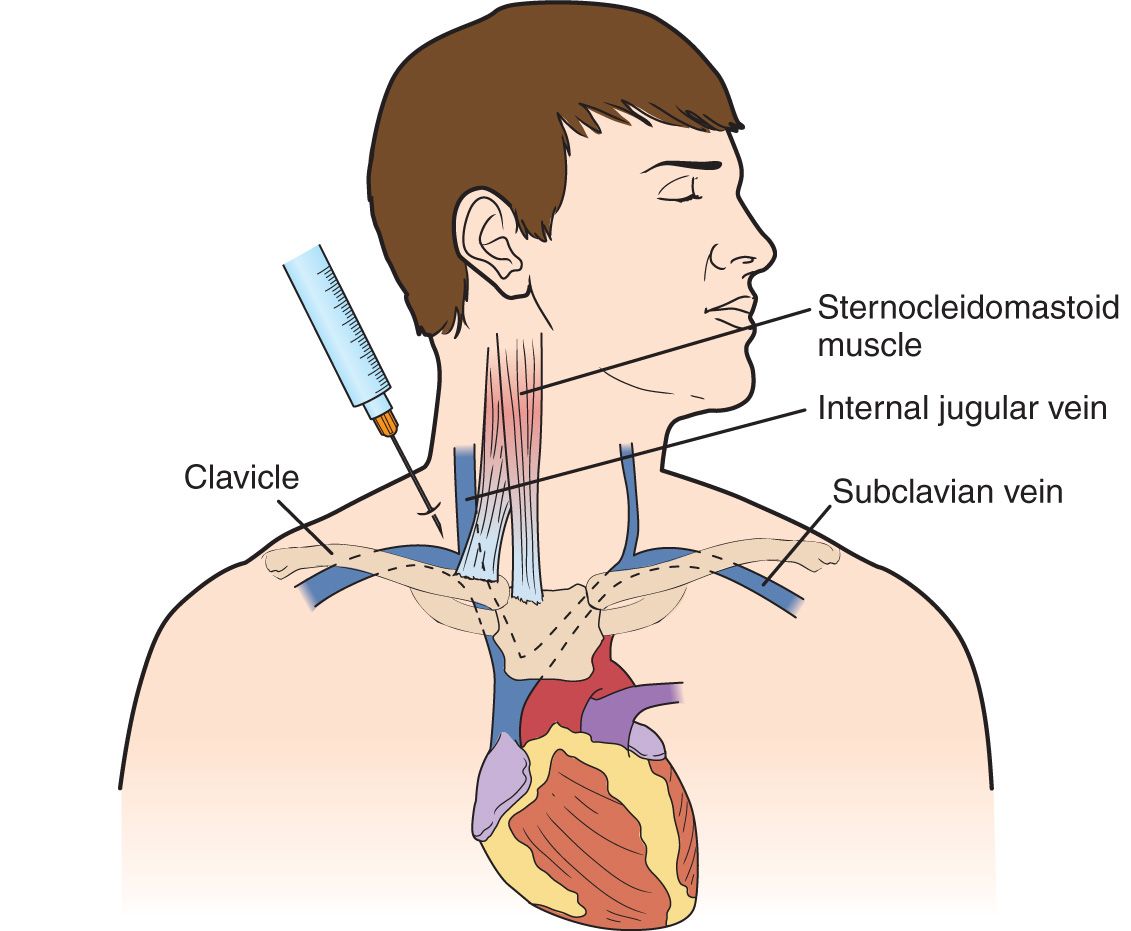

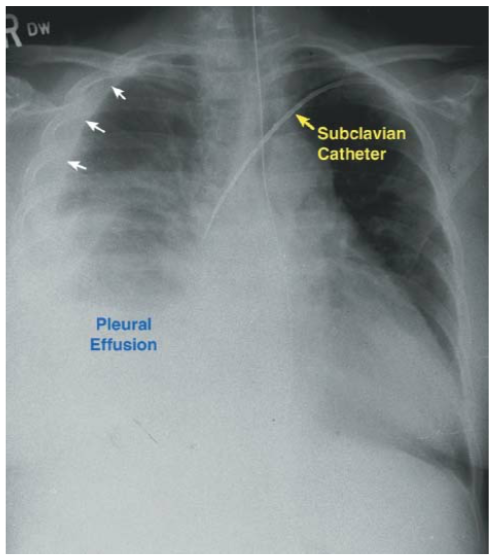

Subclavian vein

- If you’re going for the subclavian, might I suggest using an ultrasound3? Complications of subclavian access include pneumothorax and nerve injury, both of which occur less frequently with the use of an ultrasound machine as a guide.

- If your patient will need a hemodialysis site, try to stay away from the subclavian vein on the ipsilateral site of the arteriovenous fistula, since subclavian stenoses commonly occur4.

- Subclavian vein access is generally more comfortable for patients compared to other sites.

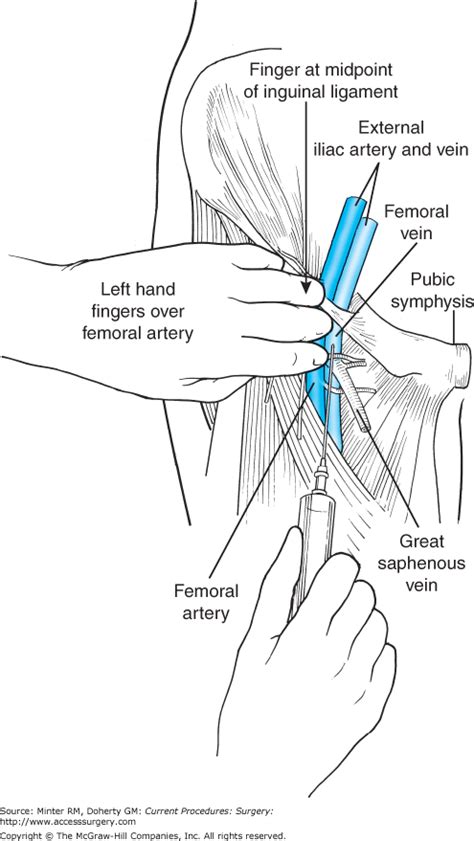

Femoral vein

- Femoral vein thrombosis is a common complication, but this is often clinically silent5.

- Avoid using the femoral vein during cardiac arrests, since drug delivery can be delayed!

- Do not get femoral access in patients with DVTs6.

- Femoral vein access is contraindicated in patients with abdominal trauma, since the IVC could be disrupted6!

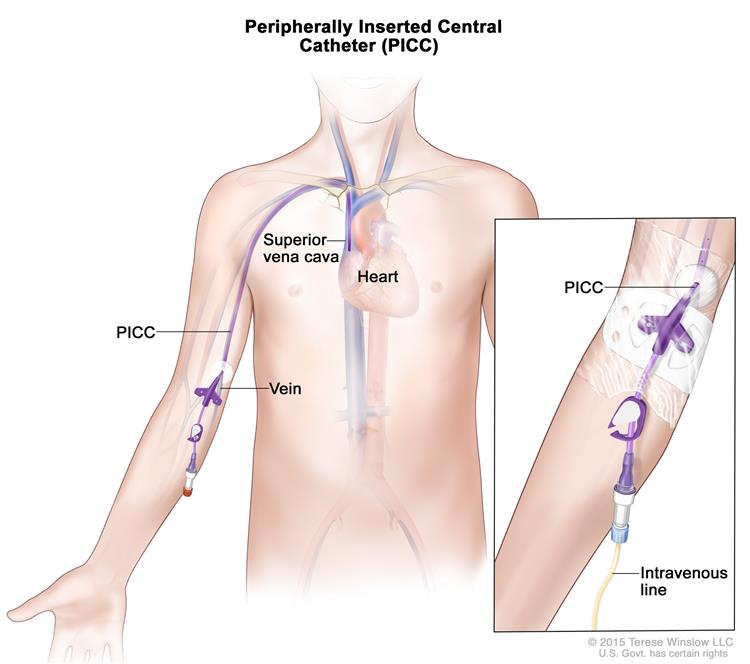

Peripherally inserted central catheters

- Honestly these are probably the way to go if you have the option. Easy to do (especially with ultrasound) with minimal risks.

- The most common complication is PICC-associated thrombosis, particularly in cancer patients7.

Complications

Air embolus

- In spontaneous respiration, breathing creates a negative pressure gradient that, combined with a point of air entry above the right atrium, creates the risk of introducing air into the vasculature and causing a fatal embolus.

- A large enough air embolus can cause heart failure, leaky capillary pulmonary edema, and if there’s a patent foramen ovale, an acute stroke8.

- Your patient may not show any symptoms, or may start having difficulty breathing with a cough.

- Physical exam may reveal a murmur before cardiovascular collapse8.

- Diagnosis is clinical, but if a TEE is available, you can use it with Doppler to try to see air bubbles in the heart.

- There’s no specific treatment other than stopping the track of air in the catheter. Provide cardiorespiratory support!

Pneumothorax

- Generally speaking, get a chest x-ray during forced expiration while the patient is sitting up (though with sick patients this can be hard to do).

- If it’s not possible to sit patients up, you can perform an ultrasound instead9.

- Pneumothoraces may not be immediate! Keep suspecting them if a patient develops symptoms later on.

Indwelling catheters

Replacements

Peripheral catheters might cause phlebitis. You don’t have to change peripheral catheters unless there are clinical signs of phlebitis though. Some guidelines suggest changing peripheral lines every few days, but I imagine this is institution-dependent.

Try not to change central catheters too frequently, as doing so can actually cause more complications than it prevents10. Erythema around the site by itself isn’t even an indication to change the catheter (but suspicion of infection can be!).

Noninfectious complications

One of the most common complications is catheter occlusion, which can result from thrombotic occlusion or non-thrombotic occlusion. Of these two, thrombosis is more likely. You should try to make the catheter patent again with alteplase, which has a high success rate without increasing bleeding risk11. Non-thrombotic occlusion could result from infusate drug precipitates, and you can usually flush these clean.

Another important complication to beware is the venous thrombosis, which is usually clinically silent. Unsurprisingly, these occur at far higher rates among cancer patients, who are already hypercoagulable at baseline and may require central lines for a long period of time.

Diagnose with compression ultrasound. You might get a D-dimer, but this information will be unlikely to help, since sick patients often have elevated D-dimers anyway. Might as well skip that test.

Unless anticoagulation therapy is contraindicated and symptoms aren’t terrible, you can consider leaving the catheter in!

Ah crap I poked a hole in my patient

Yikes12. This happens more often with left-sided central venous access, and leads to nonspecific symptoms like cough and chest pain. Chest x-ray demonstrates widening of the mediastinum, along with pleural effusions. If you really want to, you can tap the pleural effusate and see what the fluid is made of…in theory it will be similar to whatever you intended on infusing into the patient. You could also infuse some dye and see if it makes it into the pleural effusion. But the best thing to do now is to remove the catheter, and – if you suspect infection – antibiotics.

Cardiac tamponade

This is severe, and can lead to abrupt decompensation. Diagnose quickly with an ultrasound that shows pericardial effusion, and perform a pericardiocentesis.

Infections

Probably the most common way catheter-related infections take hold is via skin flora introduced into the subcutaneous track created by the catheter. We worry about microbes forming biofilms on catheters because it takes a huge dose of antibiotics to get rid of them compared to free-living bacteria13.

Diagnosis

There are 3 culture methods and criteria for diagnosis of culture-related bloodstream infection (which is to be distinguished from culture-associated bloodstream infection!)14.

| Culture method | Diagnostic criteria |

|---|---|

| Culture of tip | Same organism on tip and in peripheral blood |

| Quantitative blood cultures | Same organism in peripheral and catheter blood, and >3x in catheter blood |

| Time to positive culture | Same organism in peripheral and catheter blood, and 2h less time to positive culture in catheter blood |

Treatment

In general, treat gram-positive organisms with vancomycin (and convert to daptomycin if there’s a concern of VREs). For concern of gram-negative organisms, treat with carbapenems or piperacillin-tazobactam. Treat candidemia with fluconazole.

Persistent infections

Consider the possibility of 1) suppurative thrombophlebitis or 2) endocarditis.

In suppurative thrombophlebitis, the most common offending organism is Staph aureus, and the patient may present with signs such as purulent drainage, limb swelling, cavitary lesions in the lungs, and embolic lesions in the hand. Remove the offending catheter and treat with long-term antibiotics. Persistent and refractory septicemia may require surgical removal of thrombi.

In endocarditis, evaluate for a new heart murmur, and diagnose with transesophageal ultrasound.