Why are notes at the extremes of a digital keyboard slightly off-tune?

Last night, a friend and I were jamming on the keyboard when I noticed an interesting phenomenon: the pitch of the note at the very bottom of the keyboard seemed ever so slightly flat, and the pitch at the top of the keyboard just a little sharp. As this is an electric keyboard, I doubted that this was a flaw with tuning, and instead it seemed to be an intentional design choice. In theory, all semitones have a frequency ratio of \(\sqrt[12]{2}\); however, this finding suggests that particularly at the extremes of a piano, the ratio breaks down (by design!). Further reading into how piano tuning works revealed a fascinating tangent into the physics and intuition behind stretch tuning.

To begin, every piano string (as does every string in general) has a fundamental frequency; that is, the lowest frequency at which a string can vibrate. For a middle A on the piano, this corresponds to 440 Hz. Every other frequency at which this string can vibrate (when held fixed at its two ends) is an integer multiple of its fundamental frequency (e.g. 880, 1320, 1760, and so on). These higher frequencies are referred to as harmonics. When a piano hammer hits a particular string, the resulting tone is composed of the fundamental and a combination of its harmonics.

A pianist’s tessitura is typically composed of roughly three octaves. In the middle of this range, the strings can be approximated to be nearly perfect (that is, the string can be approximated to have little resistance to bending or rolling), and the fundamentals and harmonics adhere pretty closely to this rule.

However, at the very low end of the piano, the string diameter is markedly thicker, and therefore deviates from this approximation. If we were to have a low A string whose fundamental frequency is 55 Hz, the imperfections of the string may create harmonics that are slightly off from the predicted values. For example, a 55 Hz string may create overtones at 113 Hz instead of 110; 170 Hz instead of 165; etc. The difference between the frequencies of the overtones, when played together with higher octaves of A, forms inharmonicity and therefore a phenomenon called “beating”, whereby the human ear can perceive slight differences in frequencies as a periodic variation in volume. Similarly, the high A string is imperfect in that it must be coated and made thicker to withstand the pressure of the piano hammer; a perfect high A string would be too thin to survive!

As an interesting aside, the concept of musical beating forms the basis of binaural beats, an auditory illusion where two pure tones with a very small difference in frequency are introduced one in each ear of a listener. The listener will then perceive a third tone at a frequency of the \(\Delta f\) between the two actual tones.

Given the relative imperfections of the strings near the bottom and top of the piano range, a piano tuner must “overstretch” these strings in order to compensate for the differences in the most important harmonics. To do this, the piano tuner adjusts the fundamentals of these strings until the beating caused by inharmonicity effectively disappears.

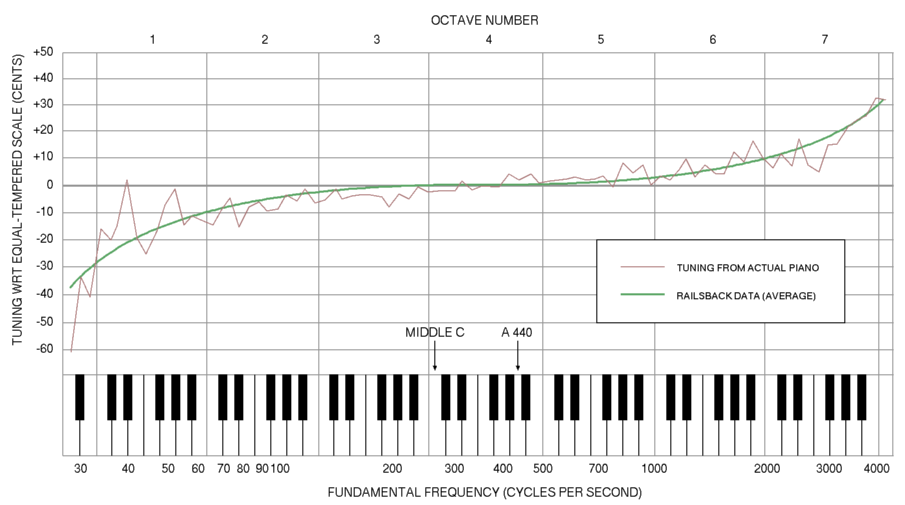

The Railsback curve below demonstrates the difference between normal piano tuning and a perfect equal-tempered scale.

Time will tell whether I will be able to unhear this phenomenon while playing the piano anytime soon.